Art Work of Scenes in the Valley of Virginia

The Hudson River School was a mid-19th century American art movement embodied past a grouping of landscape painters whose artful vision was influenced by Romanticism. The paintings typically draw the Hudson River Valley and the surrounding area, including the Catskill, Adirondack, and White Mountains. Works by the second generation of artists associated with the school expanded to include other locales in New England, the Maritimes, the American Westward, and S America.

Overview [edit]

The proper noun Hudson River School is thought to take been coined past New York Tribune art critic Clarence Cook or by landscape painter Homer Dodge Martin.[1] It was initially used disparagingly, as the manner had gone out of favor after the plein-air Barbizon School had come up into vogue among American patrons and collectors.

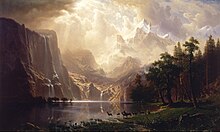

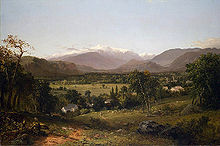

Hudson River Schoolhouse paintings reflect 3 themes of America in the 19th century: discovery, exploration, and settlement.[2] They also depict the American landscape as a pastoral setting, where human beings and nature coexist peacefully. Hudson River School landscapes are characterized by their realistic, detailed, and sometimes idealized portrayal of nature, often juxtaposing peaceful agriculture and the remaining wilderness which was fast disappearing from the Hudson Valley only as information technology was coming to be appreciated for its qualities of ruggedness and sublimity.[3] In full general, Hudson River Schoolhouse artists believed that nature in the form of the American landscape was a reflection of God,[four] though they varied in the depth of their religious conviction. They were inspired past European masters such as Claude Lorrain, John Constable, and J. 1000. W. Turner. Several painters were members of the Düsseldorf schoolhouse of painting, others were educated by German Paul Weber.[5]

Founder [edit]

Thomas Cole is mostly acknowledged as the founder of the Hudson River School.[six] He took a steamship up the Hudson in the autumn of 1825, stopping first at West Betoken then at Catskill landing. He hiked w high into the eastern Catskill Mountains of New York to paint the first landscapes of the area. The get-go review of his work appeared in the New York Evening Mail service on Nov 22, 1825.[seven] Cole was from England and the brilliant fall colors in the American landscape inspired him.[half-dozen] His close friend Asher Brown Durand became a prominent effigy in the schoolhouse, as well.[eight] A prominent chemical element of the Hudson River School was its themes of nationalism, nature, and holding. Adherents of the motility besides tended to exist suspicious of the economic and technological development of the age.[nine]

2d generation [edit]

The second generation of Hudson River Schoolhouse artists emerged after Cole'south premature death in 1848; its members included Cole's prize pupil Frederic Edwin Church, John Frederick Kensett, and Sanford Robinson Gifford. Works past artists of this second generation are often described as examples of Luminism. Kensett, Gifford, and Church were also amid the founders of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York Urban center.[x]

Near of the finest works of the second generation were painted betwixt 1855 and 1875. Artists such as Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt were celebrities during that time. They were both influenced by the Düsseldorf school of painting, and Bierstadt had studied in that city for several years. Thousands of people would pay 25 cents per person to view paintings such every bit Niagara [xi] and The Icebergs.[12] The epic size of these landscapes was unexampled in earlier American painting and reminded Americans of the vast, untamed, and magnificent wilderness areas in their country. This was the flow of settlement in the American West, preservation of national parks, and establishment of green city parks.

Female artists [edit]

Several women were associated with the Hudson River School. Susie M. Barstow was an avid mountain climber who painted the mountain scenery of the Catskills and the White Mountains. Eliza Pratt Greatorex was an Irish-born painter who was the second woman elected to the National University of Design. Julie Hart Beers led sketching expeditions in the Hudson Valley region before moving to a New York City art studio with her daughters. Harriet Cany Peale studied with Rembrandt Peale and Mary Claret Mellen was a student and collaborator with Fitz Henry Lane.[xiii] [14]

Legacy [edit]

Hudson River School art has had minor periods of resurgence in popularity. The school gained interest afterwards World War I, probably due to nationalist attitudes. Interest declined until the 1960s, and the regrowth of the Hudson Valley[ vague ] has spurred further interest in the movement.[15] Historic house museums and other sites dedicated to the Hudson River School include Olana State Historic Site in Hudson, New York, the Thomas Cole National Celebrated Site in the boondocks of Catskill, the Newington-Cropsey Foundation's historic house museum, art gallery, and research library in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York, and the John D. Barrow Art Gallery in the hamlet of Skaneateles, New York.

Collections [edit]

Public collections [edit]

One of the largest collections of paintings by artists of the Hudson River School is at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut. Some of the most notable works in the Atheneum's collection are thirteen landscapes by Thomas Cole and eleven by Hartford native Frederic Edwin Church. They were personal friends of the museum's founder, Daniel Wadsworth.

Other collections [edit]

- Albany Constitute of History & Art in Albany, New York

- Arnot Fine art Museum in Elmira, New York

- Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts

- Brooklyn Museum in Brooklyn, New York

- Corcoran Gallery of Art, in Washington, DC

- Crystal Bridges Museum, in Bentonville, Arkansas

- Cummer Museum of Art & Gardens, in Jacksonville, Florida

- Detroit Institute of Arts in Detroit, Michigan

- Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York

- Frances Lehman Loeb Art Eye, in Poughkeepsie, New York

- Fruitlands Museum in Harvard, Massachusetts

- Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Haggin Museum in Stockton, California

- Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, New York

- Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, Tennessee

- Louvre Museum in Paris, France

- Mabee-Gerrer Museum of Art in Shawnee, Oklahoma[16]

- Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park in Woodstock, Vermont

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, in Manhattan, New York

- Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in Boston, Massachusetts

- Museum of White Mountain Art in Jackson, New Hampshire

- National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC

- Newark Museum in Newark, New Jersey

- Newington-Cropsey Foundation in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York

- New-York Historical Society, in Manhattan, New York

- Olana State Historic Site, in Hudson, New York

- St. Johnsbury Archives, in St. Johnsbury, Vermont

- Westervelt Warner Museum of American Fine art, in Tuscaloosa, Alabama

- Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, in Madrid, Spain

- The Heckscher Museum of Art, in Huntington, New York

- Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, in Richmond, Virginia

- Worcester Art Museum, in Worcester, Massachusetts

- Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Connecticut

The Newington-Cropsey Foundation, in their Gallery of Fine art Edifice, maintains a enquiry library of Hudson River School art and painters, open to the public past reservation.[17]

Notable artists [edit]

See also [edit]

- Düsseldorf school of painting

- History of painting

- Landscape art

- List of Hudson River School artists

- Macchiaioli

- Romanticism

- National Romanticism

- Western painting

- White Mountain fine art

- Young America Movement

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ Howat, John Chiliad (1987). American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harry North. Abrams, Inc. pp. 3, 4.

- ^ Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin; Ellis, Amy; Miesmer, Maureen (2003). Hudson River School: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art . Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. p. vii. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ "The Panoramic River: the Hudson and the Thames". Hudson River Museum. 2013. p. 188. ISBN978-0-943651-43-9 . Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ "The Hudson River School: Nationalism, Romanticism, and the Celebration of the American Mural". Virginia Tech History Department. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ John K. Howat: American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River Schoolhouse, Due south. 311

- ^ a b O'Toole, Judith H. (2005). Different Views in Hudson River School Painting. Columbia University Press. p. 11.

- ^ Boyle, Alexander. "Thomas Cole (1801–1848) The Dawn of the Hudson River School". Hamilton Auction Galleries. Retrieved 19 Dec 2012.

- ^ "Asher B. Durand". Smithsonian American Art Museum: Renwick Gallery. Smithsonian Museum. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ^ Angela Miller, The Empire of the Eye (1996); Alfred 50. Brophy, Holding and Progress: Antebellum Landscape Art and Property, McGeorge Law Review 40 (2009): 601-59.

- ^ Avery, Kevin J. "Metropolitan Museum of Art: Frederick Edwin Church". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ "Corcoran Highlights: Niagara". Corcoran Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Potter, Russell A. "Review of 'The Voyage of the Icebergs: Frederic Edwin Church's Arctic Masterpiece'". Rhode Isle College. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ^ Dobrzynski, Judith H. "The Grand Women Artists of the Hudson River School". Smithsonian. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Remember the Ladies: Women Artists of the Hudson River School". Resource Library. Traditional Fine Arts System, Inc. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Zimmer, William (October 17, 1999). "Hudson River School Merely Keeps on Rolling". The New York Times . Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- ^ White, Mark Andrew (2002). Progress on the Country: Industry and the American Landscape Tradition. Oklahoma City, OK: Melton Fine art Reference Library. pp. 6–13. ISBN0-9640163-ane-1.

- ^ Hershenson, Roberta (Nov 7, 1999). "Work Is in Dispute, but Cropsey's Home Is Open". The New York Times . Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Allaback, Sarah. "19th Century Painters: Hudson River School" (PDF). 2006. Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2013. Retrieved nineteen December 2012.

- ^ Rickey, Frederick. "Robert W. Weir (1803–1889)". United States Military Academy. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

Sources

- American paradise: the globe of the Hudson River school . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1987. ISBN978-0-87099-496-8.

- Avery, Kevin J., & Kelly, Frank (2003). Hudson River school visions: the landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN978-0-300-10184-three.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ferber, Linda S. The Hudson River School: Nature and the American Vision. New-York Historical Guild, 2009.

- Sullivan, Mark West. The Hudson River School: An Annotated Bibliography. Metcuhen, NJ; Scarecrow Press, 1991.

- Wilmerding, John. American Light: The Luminist Motion, 1850–1875: Paintings, Drawings, Photographs. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., 1980. ISBN 9780064389402. OCLC 5706999.

External links [edit]

- The Hudson River School, American Art Gallery

- The Hudson River Schoolhouse, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- National Park Service overview of Hudson River School

- Wadsworth Atheneum's Hudson River School Collection

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hudson_River_School