Continuity in China From 1900 Present

GDP per capita in China (1913–1950)

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in 1912, China underwent a period of instability and disrupted economic activity. During the Nanjing decade (1927–1937), China advanced in a number of industrial sectors, in particular those related to the military, in an effort to catch up with the west and prepare for war with Japan. The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) and the following Chinese civil war caused the retreat of the Republic of China and formation of the People's Republic of China.[1]

The Yuan Shikai "dollar" (yuan in Chinese), issued for the first time in 1914, became a dominant coin type of the Republic of China.

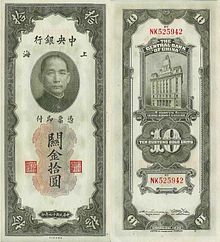

A bill from 1930, early ROC

The Republican era was a period of turmoil. From 1913 to 1927, China disintegrated into regional warlords, fighting for authority, causing misery and disrupting growth. After 1927, Chiang Kai-shek managed to reunify China. The Nanjing decade was a period of relative prosperity despite civil war and Japanese aggression. The government began to stabilize tax collection, establish a national budget, sponsor the construction of infrastructure such as communications and railroads, and draw up ambitious national plans, some of which were implemented after 1949. In 1937, the Japanese invaded and laid China to waste in eight years of war. The era also saw boycott of Japanese products. After 1945, the Chinese civil war further devastated China and led to the withdrawal of the Nationalist government to Taiwan in 1949. Yet the economist Gregory Chow summarizes recent scholarship when he concludes that "in spite of political instability, economic activities carried on and economic development took place between 1911 and 1937," and in short, "modernization was taking place." Up until 1937, he continues, China had a market economy which was "performing well", which explains why China was capable of returning to a market economy after economic reform started in 1978.[2]

There have been two major competing interpretations (traditionalist vs revisionist) among scholars who have studied China's economy in the late Qing and Republican period.[3]

The traditionalists (mainly historians like Lloyd Eastman, Joseph Esherick and others) view China's economic performance from the early 19th to the middle 20th century as abysmal. They view the traditional economic and political system during the late Qing and Republican periods as being unable to respond to the pressures of the West and inhibiting economic growth. These scholars stress the turning point in 1949 when the PRC is founded as acting as allowing for the political and economic revolution required that led to fast economic growth.[ citation needed ]

The revisionists (mainly economists like Thomas Rawski, Loren Brandt and others) view the traditional economy as mostly successful with slow but steady growth in GDP per capita after the late 19th century. These scholars focus on the continuity of between features of the traditional economy and the PRC economy with its rapid growth. They believe that the PRC built upon the favourable conditions that existed during the Republican and late Qing periods, which allowed for the fast economic growth of the period.[4]

Civil war, famine and turmoil in the early republic [edit]

The early republic was marked by frequent wars and factional struggles. Following the presidency of Yuan Shikai to 1927, famine, war and change of government was the norm in Chinese politics, with provinces periodically declaring "independence". The collapse of central authority caused the economic contraction that was in place during final Qing decades to speed up, and was only reversed after China reunified in 1927 under the rule of Nationalist Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.[5]

Development of domesticated industries [edit]

Chinese domestic industries developed rapidly after the downfall of the Qing dynasty, despite turmoil in Chinese politics. Development of these industries peaked during World War I, which saw a great increase in demand for Chinese goods, which benefitted China's industries. In addition, imports to China fell drastically after total war broke out in Europe. For example, China's textile industry had 482,192 needle machines in 1913, while by 1918 (the end of the war) that number had gone up to 647,570. The number increased even faster to 1,248,282 by 1921. In addition, bread factories went up from 57 to 131.[6]

The May 4th movement, in which Chinese students called on China's population to reject purchasing products not made in China, in other words, boycotting foreign goods, also helped spur development. Foreign imports fell drastically from 1919–1921 and from 1925 to 1927.[7]

Despite the outbreak of the Great Depression in 1929, Chinese industry continued to grow and develop into the 1930s. This era is now known as the Nanking decade, a time period seen as commencing when the KMT under Chiang Kai-shek re-unified most of China, bringing a level of political stability not seen in decades. Under Chiang Kai-shek's Nanking based government, China's economy enjoyed unprecedented growth from 1927 to 1931. By 1931 however, the effects of the Great Depression began to badly impact the Chinese economy, a problem compounded further by Japan's invasion and occupation of Manchuria in the same year. Consequently, China's overall GDP, dropped to 28.8 billion in 1932. A period of stagnation and decline followed with GDP falling to 21.3 billion by 1934, after which prosperity began to return with GDP rising to 23.7 billion in 1935 as Chinese industrial output commenced a rapid recovery surpassing 1931 levels by 1936.[8]

The rural economy of the Republic of China [edit]

The rural economy retained much of the characteristics of the Late Qing. While markets had been forming since the Song and Ming dynasties, by the Republic era, Chinese agriculture was in largely geared towards producing cash crops for foreign consumption, leaving it vulnerable to the say of international markets. Key exports included glue, tea, silk, sugar cane, tobacco, cotton, corn and peanuts.[9]

The rural economy was hit much harder by the Great Depression, when domestic overproduction of agricultural goods as well as an increase in foreign imports (as agricultural goods produced in western countries were "dumped" in China) led to a collapse in food prices. In 1931, imports of rice in China amounted to 21 million bushels compared with 12 million in 1928. Other goods saw even more staggering increases. In 1932, 15 million bushels of grain were imported compared with 900,000 in 1928.[10] This increased competition caused massive declines in Chinese agricultural prices (which were cheaper) and thus the income of rural farmers. In 1932, agricultural prices were 41 percent of 1921 levels.[11] In some rural areas, incomes had fallen to 57 percent of 1931 levels by 1934.[11]

Foreign direct investment in the Republic of China [edit]

Foreign direct investment in China soared during the Republic's early years. Some 1.5 billion of investment was present in China by the beginning of the 20th century, with Russia, The United Kingdom and Germany being the largest investors. However, with the outbreak of World War I, investment from Germany and Russia stopped while the UK and Japan took a leading role. By 1930, foreign investment in China was more than 3.5 billion, with Japan leading (1.4 billion) and England at 1 billion. By 1948, however, the capital stock had halted with investment dropping to only 3 billion, with the US and Britain's leading.[12]

Currency of the Republic of China [edit]

The currency of China was initially silver-backed, but the nationalist government seized control of private banks in the notorious banking coup of 1935 and replaced the currency with the Fabi, a fiat currency issued by the ROC. Particular effort was made by the ROC government to instill this currency as the monopoly currency of China, stamping out earlier Silver and gold-backed notes that had made up China's currency. Unfortunately, the ROC government used this privilege to issue currency en masse; a total of 1.4 billion Chinese yuan was issued in 1936, but by the end of the second Sino-Japanese war some 1.031 trillion in notes had been issued.[13] This trend worsened with the resumption of the Chinese Civil war in 1946. By 1947, some 33.2 trillion of currency was issued. This was done in large part as an attempt to close the massive budget deficits brought about by the war (taxation revenue was just 0.25 billion, compared with 2500 billion in war expenses). By 1949, the total currency in circulation was 120 billion times more than in 1936.[14]

The Chinese war economy (1937–1945) [edit]

In 1937, Japan invaded China and the resulting warfare laid waste to China. Most of the prosperous east coast was quickly conquered by the Japanese, who imposed a brutal occupation on the civilian population, carrying out numerous atrocities such as the Rape of Nanjing in 1937 and random massacres of whole villages. The Japanese Air Force carried out systematic and often indiscriminate bombings of Chinese cities. Nationalist forces applied a "scorched earth" policy in response to the invasion; destroying the productive capacity of areas they had to abandon in the face Japanese military advances. The Japanese were in turn brutal in the face of any Chinese resistance they encountered, during one anti-guerilla sweep in 1942, the Japanese killed up to 200,000 civilians in a month. A further 2–3 million Chinese civilians died in a famine in Henan in 1942 and 1943. Overall the war is estimated to have killed between 20 and 25 million Chinese. It severely set back the development of the preceding decade.[15] Industry was severely hampered after the war by devastating conflict as well as the inflow of cheap American goods. By 1946, Chinese industries operated at 20% capacity and produced just 25% of pre-war output.[16]

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, the KMT government was able to recover most of the economic centers lost in Second Sino-Japanese War without subjecting them to further destruction. However this ultimately made little difference given the extent of the damage caused by the war and subsequent Japanese occupation. Initially Manchuria, which Japan had transformed into the greatest industrial center in the Far East, had escaped any large scale descruction until the Soviet invasion in the final week of the war. The Red Army rapidly overran Japanese forces, commencing a 3 month occupation defined by systemic campaign of looting and destruction. Soviet Premier Josef Stalin ordered all equipment, moveable parts, tools and even material wealth plundered from private homes, shipped back to the USSR, what could not be pillaged was to be destroyed. When the Soviets withdrew in October, ^ the result was near total. What had been China's industrial epicenter was reduced to rubble, virtually all factories had been destroyed, not a single mine was operational. Manchuria had been stripped of virtually all heavy machinery and was left without even electricity as the Soviets had dismantled or destroyed all power plants, even removing the turbines from dams.[17]

The war brought about a massive increase in government control of industries. In 1936, government-owned industries were only 15% of GDP. However, the ROC government took control of many industries in order to fight the war. In 1938, the ROC established a commission for industries and mines to control and supervise firms, as well as instilling price controls. By 1942, 70% of the capital of Chinese industry were owned by the government.[18]

Inflation spiraled during the war. The ROC government's tried unsuccessfully to curb inflation with the introduction of new currencies and failed attempts in both 1942 and 1943 to institute a general price freeze.[19] The efforts at price controls failed because China's agricultural economy was very concentrated, industry was declining, and exchange rates collapsing.[19] The result was that suppliers did not ration at stable prices, shopkeepers used their supplies for speculation, and "[e]ven productive enterprises turned from new output to speculating on stocks, while disinvestment and capital flight further undermined the production capacities."[19]

Hyperinflation, civil war and the relocation of the republic government to Taiwan [edit]

Following Japan's unconditional surrender to the allies in 1945, Chiang regained most the territory China lost in both the First and Second Sino-Japanese wars, including Taiwan where unlike the other areas to fall under foreign occupation, the Japanese (intending to eventually annex the island) left a modern educational system and economy. Chiang and the KMT then renewed their struggle with the communists.

However, the rampant corruption of the KMT, hyperinflation from the over issuing of currency and the drain on the civilian population caused by the war effort, stirred mass unrest throughout China,[20] fostering sympathy for the communist cause. Inflation had begun with the start of the Sino-Japanese War and had worsened to chronic hyperinflation by the middle of the 1940s.[21] The inflation problem was significantly based in the KMT's failure to restore revenue sources and its printing of money to finance its deficit.[21]

The communists gained significant legitimacy by defeating hyperinflation in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[22] Their development of state trading agencies reintegrated markets and trading networks, ultimately stabilizing prices. In addition, the communists' promise to redistribute land gained them support among the massive long suffering rural population.[22]

In 1949, communist forces began making rapid advancements against the collapsing Nationalist army. By October the communists had captured Beijing, with Nanjing falling soon after. The People's Republic of China was proclaimed on 1 October 1949. The KMT seemed powerless to even slow communist expansion and Chiang ordered an evacuation of the Republic of China to Taiwan, one of the only industrialized parts of China not to experience large scale destruction during the war. The relocation was intended to be only temporary as Chiang planned to regroup and reorganize his forces before returning to reconquer the mainland.[23] Despite years of planning, no such offensive would ever materialize, with the ROC existing in permanent exile on the island. Taiwan continued to prosper under the Republic of China government and came to be known as one of the Four Asian Tigers due to its "economic miracle", and later became one of the largest sources of investment in mainland China after the PRC economy began its rapid growth following Deng's reforms.[24]

See also [edit]

- Economic history of China (1949–present)

- Economic history of China before 1912

- Economy of China

- Economy of Hong Kong

- Economy of Macau

- Economy of Taiwan

- Economy of the Han dynasty

- Economy of the Ming dynasty

- Economy of the Song dynasty

References [edit]

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 616–18

- ^ Gregory C. Chow, China's Economic Transformation (2nd ed. 2007) excerpt and text search pp. 20–21.

- ^ Naughton, Barry (2007). The Chinese economy : transitions and growth. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. pp. 33–35. ISBN978-0262640640. OCLC 70839809.

- ^ Naughton, Barry (2007). The Chinese economy : transitions and growth. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN978-0262640640. OCLC 70839809.

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 613–14

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 894–95

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 897

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 1059–71

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 934–35

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 1088

- ^ a b Sun Jian, p. 1089

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 1353

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 1234–36

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 1317

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 615–16.

- ^ Sun Jian, p. 1319.

- ^ "Russian Loot Manchuria: Virtually No Heavy Machinery Left for the Chinese." Andrews, Steffan. The New York Times, published November 27, 1945. [1]. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 1237–40.

- ^ a b c Weber, Isabella (2021). How China escaped shock therapy : the market reform debate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 73. ISBN978-0-429-49012-5. OCLC 1228187814.

- ^ Sun Jian, pp. 617–18

- ^ a b Weber, Isabella (2021). How China escaped shock therapy: the market reform debate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 71. ISBN978-0-429-49012-5. OCLC 1228187814.

- ^ a b Weber, Isabella (2021). How China escaped shock therapy : the market reform debate. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 70. ISBN978-0-429-49012-5. OCLC 1228187814.

- ^ Gary Marvin Davison (2003). A short history of Taiwan: the case for independence. Praeger Publishers. p. 64. ISBN0-275-98131-2.

Basic literacy came to most of the school-aged populace by the end of the Japanese tenure on Taiwan. School attendance for Taiwanese children rose steadily throughout the Japanese era, from 3.8 percent in 1904 to 13.1 percent in 1917; 25.1 percent in 1920; 41.5 percent in 1935; 57.6 percent in 1940; and 71.3 percent in 1943.

- ^ Top 10 Origins of FDI Archived 4 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine US-China Business Council, February 2007

Bibliography and further reading [edit]

- Chow, Gregory C. China's Economic Transformation (2nd ed. 2007) excerpt and text search

- Eastman Lloyd et al. The Nationalist Era in China, 1927–1949 (1991) excerpt and text search

- Fairbank, John K., ed. The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 12, Republican China 1912–1949. Part 1. (1983). 1001 pp., the standard history, by numerous scholars

- Fairbank, John K. and Feuerwerker, Albert, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China, 1912–1949, Part 2. (1986). 1092 pp., the standard history, by numerous scholars

- Ji, Zhaojin. A History of Modern Shanghai Banking: The Rise and Decline of China's Finance Capitalism. (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2003 ISBN 0765610027). 325pp.

- Rawski, Thomas G. and Lillian M. Li, eds. Chinese History in Economic Perspective, University of California Press, 1992 complete text online free

- Rawski, Thomas G. Economic Growth in Prewar China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989. 448pp ISBN 0520063724.

- Rubinstein, Murray A., ed. Taiwan: A New History (2006), 560pp

- Shiroyama, Tomoko. China during the Great Depression: Market, State, and the World Economy, 1929–1937 (2008)

- Sun, Jian, 中国经济通史 Economic history of China, Vol 2 (1840–1949), China People's University Press, ISBN 7300029531, 2000.

- Young, Arthur Nichols. China's nation-building effort, 1927–1937: the financial and economic record (1971) 553 pages full text online

External links [edit]

- Applet-magic.com: The Economic History and the Economy of China

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_history_of_China_%281912%E2%80%931949%29